In the spring of 1992, I was finishing my first year at USC (having transferred from Cal State Fullerton the previous fall).

Specifically, however, on Wednesday, April 29, 1992, I worked at my job as a teller at the First Interstate Bank branch in Claremont, Calif. Why Claremont? Well, my college girlfriend attended one of the Claremont Colleges, and though I had an off-campus apartment at the corner of Severance and Adams near the USC campus, I tended to spend a lot of time with her.

When I left my shift that afternoon, I headed over to her dorm to study for my first final of the spring semester, which was scheduled for 8 a.m. Thursday morning. The plan was to wait for traffic to die down and then head out to USC that evening to grab a decent night’s sleep before the test.

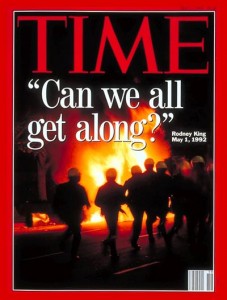

As most of you know, that plan was torn to shreds by 12 jurors in a Simi Valley courtroom and the enraged reaction of thousands of Los Angeles residents — that April 29 will forever be known as the first day of the 1992 L.A. Riots.

***

When I arrived at the dorm, many of the young women who lived there were watching a TV in a rec room, as the local news covered initial reactions to the late afternoon verdict. Many of us in the room were as stunned as those who were being interviewed on TV. As the coverage transitioned to various outbreaks of protest, many of us in the room voiced our agreement with those protests. Then, the helicopters started flying over Florence and Normandie, and everything changed. Reginald Denny … Damian “Football” Williams … burning, burning, burning. And you knew this could really get out of hand.

As we moved into my girlfriend’s room to continue watching the news coverage across all channels, things got more and more violent, as the protests moved from voice to action. And, once the idea of public mayhem became conceivable, it sure didn’t hurt that many people who lived outside the confines of the law to begin with took advantage of the situation and exacerbated things even further. If you were alive and in Southern California during this time, you know how it made you feel, you know who you blame, you know what you think, so I won’t preach to you. But the truth of the L.A. Riots — why they happened, why they were so out of control, who was to blame, what’s changed since — is obviously more multifaceted than simple statements like “racist cops beat black man and walk” or “decades of police brutality come home to roost” or “local criminals take advantage of widespread lawlessness to wreak havoc on city.”

What I will tell you is that I was still trying to study for that final that night, all while watching the TV coverage and listening to the third game of the Lakers’ playoff series against the Portland Trailblazers on my Walkman, since there was no cable TV in the dorm rooms. The game was taking place inside the Great Western Forum in Inglewood (near the epicenter of the riots). Blissfully unaware of what was occurring outside (in an era before cell phones — let alone smartphones and social media), fans watched the underdog Lakers upset the Blazers in overtime (remember, this was the spring after Magic Johnson retired after testing HIV positive) to extend a first-round series. The only clue as to what was happening, I recall, was late in the fourth quarter, when legendary Laker announcer Chick Hearn told listeners/viewers that the Forum message board was flashing that no traffic after the game would be allowed to head east toward the 110 freeway. “All traffic must head west toward the 405. That’s a strange message, but I am only reporting what I see,” I remember Hearn saying. The dissonance between listening to that game and keeping an eye on the violence tearing apart the city on television was, suffice it to say, shocking.

During all of this violence, the news had reported that the USC campus was unscathed by rioters, that the area just around the campus was still reasonably quiet in the center of this storm. And, by 10:30 p.m., there was no announcement from the school on a postponement of finals that were scheduled for Thursday. Nor by 11:30 … or 12:30 a.m. Common sense told me that there was no way the school could function normally on Thursday, but I wasn’t going to risk a grade. So I tried going to sleep, but to no avail with what was happening on TV. By 4 a.m., I tried calling the general phone number for campus to see if any announcement had been made — school closure announcements had been part of the news coverage all night, but there was still no word from USC — but got no answer. I truly had no choice but to get in my car and drive straight toward the campus.

At about 5:20 a.m., I had just passed the 710 freeway, driving west on the 10, when a reporter on KFWB finally said those words I’d been waiting so long for: “USC has announced that final exams scheduled for today and Friday are postponed indefinitely.” While definitely irritated that the announcement had come only at that moment, what I actually really was at that moment was exhausted. So, I made a decision that could have been one of the worst I’d ever made, but instead turned out only to be one of the most interesting: I just wanted to go to sleep and I was about 10-12 minutes away from my apartment building’s underground parking garage and my bed. I chose to drive into the middle of the L.A. Riots.

***

I exited the freeway at Hoover. At the traffic signal, there was (and is again today) a mini-mall with an auto stereo store as it’s hub. The entire center was ablaze. There was a lone LAFD firefighter trying to fight it with a garden hose — while most remember how many in the LAPD basically threw up their hands at the rioters in a dereliction of duty, fewer recall the undermanned LAFD trying valiantly to fight hundreds of fires. I could feel the heat from the blaze through my car window. I turned and headed south on Hoover as fast as I could, reaching the light at Adams to find the Pizza Hut on the corner had turned to a pile of smoldering ashes. I turned left and, less than a block later, reached my apartment, parking my car underground and taking the elevator to my place. I crashed on my bed and didn’t wake up for five hours.

When I arose and flipped on the TV, I saw that looting had — for the most part — taken the place of violence. The rioters had simply added a step to their previous activities: they were now taking everything they could out of these stores before setting them on fire. Still, around my apartment, things were quiet. There was no traffic on the streets, and almost no people to be found anywhere. I was starving and made, in retrospect, another odd decision: I called USC to find out if any of the dining options on campus were open. I was told by the operator that EVK was open, but that I’d need my USC ID to be allowed on campus. Fine! I need to eat! I mean, sure, less than 24 hours before, I’d watched Reginald Denny get pulled out of a semi by a mob and have his head caved in. But I’d be fine driving a few blocks to USC in my uber-secure Hyundai Excel. (I am only now realizing how silly these choices were, but I hope they make for an entertaining story)

I got to campus (which was basically an armed fortress at that point, with most driveway gates closed and USC’s security team — known on campus as DPS — on patrol at each walking entrance) and to EVK, parking at a meter right outside. If you went to USC in the early 1990s, you know just how rare that opportunity was! As I walked into the dining hall, I turned and saw what I now recall as an almost cartoonish scene, reminiscent of an old Bugs Bunny cartoon, where he’s playing baseball against the Giants, who are hitting him so hard that they’re basically going around the bases in a conga line, one after another. Well, what looked like a conga line of parents in BMWs and Mercedeses were lined up outside of the entrance to the dorm, as one by one, girls would come running out of the front door with bags, throw them into the car, dive in and speed away.

After eating, I finally decided I might want to hit the road back to the safer confines of Claremont, myself. Heading up Hoover back to the freeway, that ashen former Pizza Hut was now at the center of a looting maelstrom. The minimall surrounding the Pizza Hut was home to a Payless Shoe Source and other small businesses. Dozens of people were running in and out of Payless, carting boxes of (free) $11 shoes with them. As I headed north on Hoover past the light at Adams, there was a family of four walking across the street, each member carrying at least three boxes, with the father (I can only assume) having at least four boxes stacked on each shoulder. Apparently, in whatever world they were living in at that moment, I was supposed to stop for them as they jaywalked their children who were learning how to steal things. They were stunned as I sped past them, forcing them to stop quickly — and even to drop a couple boxes of shoes in the middle of Hoover. But there was no way in hell — despite my previous choices — that I was stopping before I was on that freeway and headed out of town.

Once I got up on the 10, I saw a stunning scene on a brilliantly sunny Thursday: plumes of smoke from burning buildings in every direction. It looked like what I imagined a war zone would look like. 40 minutes later, I was back in Claremont, safely watching on television as the city unraveled even further. My main concern at that point was that my girlfriend’s family — who lived on the edges of Hancock Park, near Koreatown — was safe, and that the USC campus would remain unharmed.

***

My girlfriend and I returned to Los Angeles on Sunday to check in on her mother and step-father. We exited the 101 at Vermont and dropped down to 3rd Street, heading west. The destruction along that stretch between Vermont and Western was indescribable. I remember being so embarrassed for L.A., a city I love, that is my home. Those days of violence and lawlessness made it so easy for those media outlets across America that like to find things to hate about my city to mock it, flog it, run it down. And, in this case, with how broken the city clearly was (no matter who was to blame), there was no way to argue against it.

One light shining in the darkness was the fact that not only was USC’s campus unharmed, but that many of those who lived in the community around it rallied to make sure it went unharmed. USC’s investment in its local community — both financially and emotionally — is well known among those affiliated with the school. But to see the respect it engendered in this worst of times was rewarding. And to see the community and the school continuing and expanding that relationship two decades into the future is even more enjoyable. While those not affiliated with USC find it easy to mock the school’s location — often in lazy, ill-informed, racially-coded language — those of us who are Trojans or have some connection with the university understand how close-knit the relationship between the university and the community is.

Twenty years on, the L.A. Riots remain a defining moment in my life and in the lives of many Angelenos. While our city is, by no means, perfect, I like to believe it’s improved in the years since. And, while it would be dimwitted to say something like this could never happen again, you hope that we’re better equipped to handle the types of flashpoints that could cause another bout of civil unrest.

If you’re interested in reading more takes on the anniversary of the riots, here are some links to a few of the better stories I’ve read this week:

Christopher Wallace in The Atlantic

Hector Tobar on George Ramos and East L.A. (This one hit home when I read it yesterday. Ramos was my news reporting teacher in spring 1992, one of the best teachers I had at USC. If you had Ramos in J-school at USC, you know how much he hated bullshit and loved L.A. You also know that you covered a community beat during your semester with him. I’m still very proud to say that he told me late that semester that he assigned me to Compton because he thought I was up to the challenge.)

Patt Morrison in the L.A. Times

Photographer Kirk McCoy’s “then-and-now” photo essay in the L.A. Times

Two Gang Members Recall the Riots, as part of the Daily Beast’s excellent set of coverage.