As we’ve moved within a week of the kickoff of the 2012 college football season, I’ve decided to go back into my archives and pull a few special columns I wrote for the now defunct PigskinPost.com website during the early part of the last decade. (PigskinPost was swallowed up into the larger — and still existent — CollegeFootballNews.com after the 2003 season).

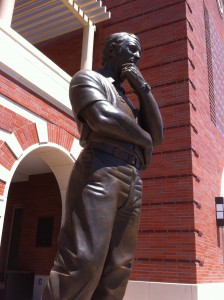

USC opened its new John McKay Center this month.

First up, a piece I wrote on legendary USC head coach John McKay as part of PigskinPost’s countdown of the Top 50 college head coaches of all time. McKay was ranked No. 12 in this countdown, and I was thrilled to be able to handle this piece at the time. Now, with the NCAA-vilified Trojans improbably ranked No. 1 by the Associated Press to start the 2012 season and the university having recently opened the glistening new John McKay Center for all of its athletes on campus, it seems apropos to kick off my own personal 2012 season by sharing this piece anew with all of you. Enjoy … and keep an eye out for a couple more throwbacks in coming days.

(Originally published April 2002 on PigskinPost.com)

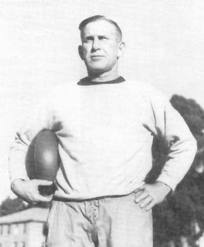

#12: John McKay, USC

“In the past, we’ve asked you men to win for your parents, your girlfriends, your school and the alumni … I think it’s about time you went out and won one for yourselves.”

— John McKay

Known for his quick wit and consistently powerful football teams, John McKay not only restored USC to its elite national status during his tenure (1960-75), he may have had more influence on how offensive football was played at the college level than any other coach in his time.

McKay modernized the “I” formation, with the tailback standing seven yards deep in the backfield, creating the “Tailback U.” image associated with Trojan football. The famed offense featured Heisman winners Mike Garrett and O.J. Simpson, as well as other classic tailbacks including Clarence Davis, Anthony Davis and Ricky Bell. While the tailbacks got the glory, opposing coaches said the key to USC’s monster rushing attack was McKay’s powerful and mobile offensive line players.

A statue of the legendary John McKay stands outside the new athletics center named after him on USC’s campus.

McKay was a huge winner. In 16 seasons, he won four national championships (1962, 1967, 1972, 1974), nine Pac-8 championships and finished in the top 10 in the national polls nine times. His career record at USC was 127-40-8, similar to Howard Jones, but against a much more wide-ranging schedule than USC played in the 1920s and ’30s. The Trojans also played in eight Rose Bowls under McKay, going 5-3.

McKay’s teams featured a veritable who’s who of college football history aside from the famous tailbacks: Ron Yary, Marvin Powell, Gary Jeter, Hal Bedsole, Lynn Swann, Bob Chandler, Charles Young, Damon Bame, Adrian Young, Charlie Weaver, Jimmy Gunn, Willie Hall, Richard (Batman) Wood, Tim Rossovich, Sid Smith, Pete Adams, Mike Battle, Artimus Parker, Marvin Cobb, Mike Rae, Jimmy Jones, Pat Haden, Sam (Bam) Cunningham, and Ben Wilson, to name just a few.

Not only are the names memorable , but some of USC’s most memorable games were played under McKay’s watch:

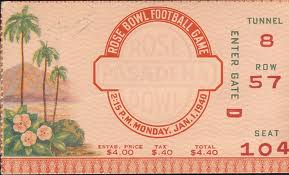

- The 1963 Rose Bowl, a 42-37 national title-clinching thriller against Wisconsin.

- A 20-17 upset of Notre Dame in 1964 that knocked the Irish from the national title race.

- A 21-20 win against UCLA in a 1967 game that decided the city championship, the Pac-8 title, the Rose Bowl representative, the national championship and the Heisman Trophy.

- Final-minute thrillers vs. UCLA (14-12) and Stanford (26-24) in 1969, and again vs. Stanford in 1973 (27-26).

- The incredible, unthinkable 55-24 comeback victory against Notre Dame in 1974.

- And the 18-17 come-from-behind triumph against Ohio State in the 1975 Rose Bowl that led to a share of the national title.

McKay grew up in West Virginia, before serving as a B-29 tailgunner in World War II. He enrolled at Purdue in 1946, playing freshman football, before transferring to Oregon the next year. McKay was an All-Coast halfback for the Ducks, teaming with friend and future All-Pro quarterback Norm Van Brocklin to form a strong offensive backfield. McKay still holds the Ducks’ single-season record for yards-per-carry average.

McKay remained at Oregon after graduation as an offensive assistant, renowned around the conference for his simple way of scouting opposing defenses.

In Jim Perry’s book on McKay, “A Coach’s Story,” McKay said:

“I wasn’t a genius. I just had a simpler method than the other scouts … a team played the defense they wanted to play 85 percent of the time. For example, Red Sanders’ UCLA teams in the mid-1950s played with what we called a 4-4, or wide-six defense. I’d watch all the other scouts draw a diagram every time UCLA lined up … I thought this was ridiculous. I knew where UCLA was lining up 85 percent of the time. So, unless they lined up differently, all I had to write was ’60’ … I could then see the game while the other scouts were laboriously writing … other scouts would miss a man or two and ask me what defense they were in, and I’d say brightly, ‘They were in 60. This guy was here and that guy was there.’ And they’d think I was a genius.”

In 1959, McKay was convinced to take an assistant’s job on USC coach Don Clark’s staff by his wife Corky, a Southern California native. When Clark resigned after the season, he recommended McKay to USC president Norman Topping, who offered McKay the job.

Much to the dismay of some alumni, USC’s new coach was unknown assistant from Oregon. McKay hardly allayed any fears in 1960, losing his debut to Oregon State, 14-0, and leading the Trojans to a 4-6 mark. The grumbling reached it peak before USC upset UCLA, 17-6, near the end of the season. McKay said at the time, “It was an important game. It only saved my job.”

McKay didn’t improve much in 1961, going 4-5-1. But his tinkering with the “I” formation that season set the stage for his first national championship team in1962.

After some solid recruiting, refinement of the “I” and an assist from Arkansas coach Frank Broyles, whose defensive scheme McKay borrowed, USC rolled to an 11-0 mark and its first national championship in 30 years.

Quarterbacks Pete Beathard and Bill Nelsen, tailback Willie Brown, fullback Wilson and 6-5 wideout Bedsole led a speedy USC team to a 261-92 scoring margin. The season’s highlights included a 14-0 shutout of recently dominant Washington, a 14-3 win against UCLA and a 25-0 victory over Notre Dame in Los Angeles.

The season was capped off in a thrilling Rose Bowl against Wisconsin. USC led 42-14, before Badger QB Ron Vanderkelen completed 18 of 22 passes in the fourth quarter to lead a rally that fell five points short, 42-37.

After the game, the normally calm McKay was incensed about the media’s reaction to the Wisconsin rally. As recounted in Mal Florence’s 1980 book, “The Trojan Heritage,” he told his team, “Wisconsin! That’s all they’re talking about. In a few minutes, the writers will be in here telling you men how lucky you were to pull this one out. Don’t you believe it. You’re the best damn team I ever saw. Our intention was to win today — and what does the scoreboard say? Who was picked to lose to the Big-10 powerhouse? We were. Ask the experts which team scored 42 points. You did, and you earned every one of them. We came in No. 1. They came in No. 2 and lost. That makes us still No. 1!”

Though McKay’s temper did run hotter than most of his sportswriter buddies at the time told their readers, the old coach’s sense of humor was his calling card. After McKay passed away last year, a number of obituaries focused on his humor while coach of the hapless Tampa Bay Buccaneers. But that humor was a staple of his time at Southern California.

Talking about one of his lesser skilled offensive lines at USC, McKay told a writer, “You’ve heard of the Seven Blocks of Granite? Last year, we had the seven blocks of cement.” Often, McKay would enter his morning press conferences announcing, “O.K. gang, we can begin. The star is here.”

He had no bigger fans than the L.A. sports press. In fact, McKay would spend hours diagramming plays for assistants and sportswriters at his own special table at Julie’s, the famous former hangout for Trojans near the USC campus and the Coliseum. McKay was so fond of his table at Julie’s, when he left USC for the Bucs, he had it shipped to his new watering hole in Tampa with the restaurant’s approval.

No one was safe from McKay’s quips and barbs. He even zinged his wife now and again. Once, when asked if emotion played a big role in the outcome of football games, he said, “Nobody is more emotional than my wife, and she’s a lousy football player.”

Of course, his wife was also his most trusted friend and greatest protector. When asked what he thought of people calling him arrogant, McKay shot back, “I don’t think of myself as arrogant. I think of myself as a friendly horse’s ass. What I don’t like is when a sportswriter doesn’t like me and writes that nobody likes me. That ticks my wife off.”

After the 1962 title season, the Trojans welcomed a sophomore tailback, Mike Garrett, into the fold. 1963 was the first of back-to-back 7-3 seasons. In 1965, the senior Garrett led USC to a 7-2-1 mark, winning the Heisman. But key losses to Washington and UCLA in Garrett’s three seasons kept the Trojans from playing in a Rose Bowl during his career.

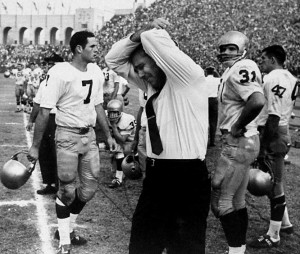

Ara Parseghian’s reaction to USC’s stunning 1964 come-from-behind win against the Irish would become rather familiar over the next 10 years.

The shining moment of this era came at the close of the 1964 season, when USC rallied from a 17-0 halftime deficit to top-ranked Notre Dame at the Coliseum.

According to Florence, at halftime, McKay lightened the mood in a disconsolate Trojan locker room, telling the team, “Gentlemen, if we don’t score more than 17 points in the second half, we don’t have a chance.”

When Rod Sherman hauled in Craig Fertig’s 15-yard pass in the final minute, McKay had foiled Irish coach Ara Parseghian (not for the last time) and the Irish’s bid for the national championship, 20-17.

After the game, Florence wrote, the Catholic McKay told the press, “Father (Theodore) Hesburgh (Notre Dame’s president at the time) congratulated me and told me, ‘That wasn’t a very nice thing for a Catholic to do.’ I told him, “Father, it serves you right for hiring a Presbyterian (Parseghian).”

McKay’s battles with Parseghian were the stuff of legend. During the 1940s and ’50s, the USC-Notre Dame series had become one-sided in favor of the Irish. But McKay turned things around in the fabled rivalry after losing to Notre Dame in his first two seasons (and then suffering a 51-0 trouncing in 1966).

Although McKay denied the story, he reportedly said after that 1966 game that Notre Dame would never beat him again. In his last nine seasons at USC, McKay was 6-1-2 against ND, leaving Troy with an overall record of 8-6-2 against the Irish.

1967 was McKay’s next season of greatness. It also marked the beginning of a three-year stretch that saw USC go 29-2-2, win the 1967 national championship, finish second and third in the polls the next two seasons, and play in three straight Rose Bowls.

O.J. Simpson arrived from San Francisco City College as a junior in 1967. He averaged 154 yards rushing per game and USC’s defense allowed just 87 points in 11 games in 1967, going 10-1 to win the championship.

McKay led the Trojans to a destruction of their South Bend jinx in 1967. Led by Simpson’s running and seven interceptions, USC notched a 24-7 victory, its first in Notre Dame Stadium in 28 years — and payback for the 51-0 thrashing by the Irish a year earlier.

OJ Simpson’s famous cutback during a game-winning 64-yard touchdown run that defeated No. 1 UCLA, 21-20, in 1967.

The 1967 USC-UCLA game, one of the all-time college football classics, featured a top-ranked Bruin squad and the third-ranked Trojans (who had fallen from No. 1 after a 3-0 loss to Oregon State the previous week). It also featured Simpson vs. Bruin quarterback Gary Beban in a Heisman showdown.

The lead had changed hands four times, with UCLA clinging to a 20-14 fourth-quarter lead, when Simpson broke one of the most famous runs in college football history. The 64-yard, cutback jaunt led the Trojans to a 21-20 win. Beban won the Heisman, but O.J. and the Trojans got to the Rose Bowl, where they trampled outmatched Indiana, 14-3, to secure the national championship.

McKay’s “Cardiac Kids” of 1968-69 won or tied 12 games with fourth-quarter comebacks, cementing the coach as one of college football’s great leaders under pressure. McKay’s riverboat gambler image was boosted even further during this era, when the coach who was known for going for a two-point conversion when a simple extra point would have led to a tie became legendary for leading USC to one stunning late-game triumph after the next.

The 1968 team featured just 15 returning lettermen to augment Simpson, who won his Heisman with a 383-carry, 1,880-yard season. When reporters questioned McKay about Simpson’s workload, the coach responded famously, “The ball isn’t heavy. Anyway, O.J. doesn’t belong to a union.”

The 1968 Trojans came from behind to beat Stanford and Oregon State, and broke fourth-quarter ties to defeat Washington and Oregon. USC fell to No. 2 in the polls after it had to rally to tie Notre Dame, 21-21. But the Trojans’ magic ran out when McKay’s kids lost to No. 1 Ohio State, 27-16, in the 1969 Rose Bowl.

The ’69 USC team finished off a 10-0-1 season with a 10-3 win against Michigan in the 1970 Rose Bowl. Without Simpson, the team was now led by quarterback Jimmy Jones, tailback Clarence Davis, and a defensive line known as the Wild Bunch (Gunn, Weaver, Al Cowlings, Tody Smith and Bubba Scott).

In 1969, USC again clipped Stanford, 26-24, this time on a last-play field goal. But no “Cardiac Kids” finish competes with the 1969 UCLA game.

Both teams came into the game with 8-0-1 records, but despite a fearsome beating by the Wild Bunch, UCLA led 12-7 after QB Dennis Dummit’s short TD pass with five minutes left. Jones, who was 0-9 passing in the first half, began connecting with his receivers, finally hitting Sam Dickerson on a controversial 32-yard TD pass in the back corner of the end zone with 1:32 to play for a 14-12 win.

Matching 6-4-1 seasons in 1970 and 1971 were but a bump in the road for McKay. However, the 1970 season did feature an historic 42-21 victory at Alabama that is credited with jump-starting the desegregation of the Alabama football program.

According to legend, Paul (Bear) Bryant, a long-time McKay friend, came into the Trojan locker room after the game, congratulated the Trojan players and asked McKay if he could “borrow” sophomore fullback Sam Cunningham for a moment. Cunningham went with the Bear back to the still strikingly pallid Alabama locker room. Bryant had Cunningham stand before his team (some even say on top of a table) and told his Crimson Tide players, “This, gentlemen, is a football player.” Alabama began actively recruiting African-American athletes the next spring.

McKay also continued his mastery of Parseghian, winning 38-28 in 1970 and 28-14 in 1971. But McKay and his staff felt they had settled for less than the best in recruiting in those late ’60s years. They rededicated themselves to recruiting top-flight players after the 1970 season, seeking speed on defense to combat the growing popularity of the triple-option offense.

By 1972, McKay had found the right blend of experience and youth, speed and power. The 1972 Trojans are still considered by many the greatest team in college football history.

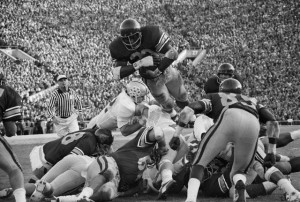

Sam Cunningham’s four airborne touchdown runs against Ohio State in the 1973 Rose Bowl helped seal USC’s 1972 national title, which many believe was the greatest single season of college football ever played.

A 12-0 record; 467 points scored (an average of 38.9 per game); 432 yards of total offense per game; never trailed in the second half; allowed just 2.5 yards per rush, with no runs longer than 29 yards.

McKay had two quality QBs, senior Mike Rae and sophomore Pat Haden. Sophomore tailback Anthony Davis became the starter at midseason. Cunningham was now a senior fullback. Tight end Charles Young and offensive tackle Pete Adams were All-Americans. Sophomore LB Richard (Batman) Wood could run a 4.5-40, unheard of for a linebacker at the time. The receiving corps included junior Lynn Swann and sophomore J.K. McKay, the coach’s son.

USC opened the season with a 31-10 trouncing of No. 4 Arkansas at Little Rock; scored 50 or more points against Oregon State, Illinois and Michigan State; hammered wishbone-oriented UCLA, 24-7; and on the strength of six Anthony Davis touchdowns, including 96- and 97-yard kickoff returns, demolished Notre Dame, 45-23.

USC then made its closing statement against Woody Hayes’ Ohio State team, drubbing the Buckeyes 42-17 in the 1973 Rose Bowl, which featured Cunningham’s four leaping touchdowns. For the first time in history, the Trojans got every first place ballot in both the AP and UPI polls.

Though he lost 12 regulars from his ’72 team, McKay directed the 1973 edition of the Trojans to a 9-2-1 mark and another Rose Bowl appearance. But 1973 also marked McKay’s only loss to Notre Dame in his last nine seasons as coach, a 23-14 defeat at South Bend. The Trojans did defeat heavily favored UCLA, 23-13, to secure their latest Rose Bowl bid, but Hayes got a measure of revenge as Ohio State toppled USC, 42-21.

McKay’s last national championship season started with an inauspicious 22-7 loss at Arkansas, and the Trojans struggled through much of the first half of the season, even tying Cal, 15-15. But once USC got rolling, they weren’t to be stopped, beating Stanford by 24, Washington by 31 and drilling UCLA, 34-9, setting up Troy’s most memorable game ever.

On Nov. 30, 1974, Parseghian’s Irish rushed to a stunning 24-0 second quarter lead over McKay’s Trojans. Anthony Davis scored a TD right before halftime to close the gap to 24-6, and then returned the second-half kickoff 102 yards to make it 24-12. Before there were two minutes elapsed in the fourth quarter, the Trojans led 55-24 — a line score that, to this day, can be found on the back of a USC football T-shirt at the Trojan bookstore.

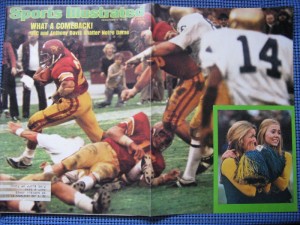

USC’s shocking 55-24 win against Notre Dame in 1974 was commemorated with a special gatefold cover in Sports Illustrated.

At halftime McKay, humorously and presciently, told his Trojans, “Gentlemen, we’re behind. Now, Davis is going to run back the kickoff for a touchdown and we’ll go from there.” Davis ran back the kickoff and the Trojans went for 49 unanswered points in less than 17 minutes.

After the shocking Trojan triumph, McKay said, “I can’t understand it. I’m gonna sit down tonight and have a beer and think about it. Against Notre Dame? Maybe against Kent State … but Notre Dame?” The game landed Davis and the Trojans on the first-ever fold-out double cover of Sports Illustrated.

But, USC’s comeback abilities weren’t sapped for the 1974 season just yet. In the closing moments, Pat Haden found McKay the younger for a 38-yard touchdown pass to close Ohio State’s lead in the 1975 Rose Bowl to 17-16. One last time, McKay rolled the dice and went for two points and the win. Haden found Sheldon Diggs with a low pass in the back of the end zone to pull out an 18-17 win and a share of the national championship.

After the game, a reporter asked McKay if he’d considered kicking the extra point and settling for a tie. McKay responded, “No, I never even thought about not going for two points. We always play it that way. Always have, always will.” It would be McKay’s last victory in the venerable Pasadena stadium.

The Trojans opened 1975 with a 7-game winning streak, including a 24-17 victory at South Bend, when Ricky Bell gained 165 yards on 40 carries. However, USC wasn’t as strong as its record (only eight starters returned from the 1974 team) and persistent rumors about McKay taking a job (and a $2-million, multi-year contract) with the NFL’s Tampa Bay expansion franchise peaked at midseason.

McKay announced after the Notre Dame game that 1975 would be his final season at USC. After the announcement, the Trojans lost their last four Pac-8 games (Cal, Stanford, Washington, UCLA). The Cal loss was USC’s first Pac-8 defeat since 1971, and the streak was the first time the Trojans had lost so many in a row since 1958.

McKay went out a winner, however, when the Trojans pulled a mild upset in the Liberty Bowl, shutting out Texas A&M, 20-0.

While much of the pro sports world remembers McKay as the sly old coach of a dismal expansion franchise (though McKay did direct the Buccaneers to the NFC Championship Game in 1979, their fourth season), it’s those who follow college football that know the real McKay.

Yes, McKay was a jokester. He was the kind of guy you’d want to sit down and have a beer with. He was the kind of guy you’d feel comfortable stewarding your son through four years of college. He was all of that. And most of all, he was a winner — standing shoulder to shoulder (if not above) his contemporaries like Hayes, Bryant, Parseghian and Michigan’s Bo Schembechler.

It’s been 27 years since he left the University Park campus, and the Trojans are still seeking his replacement. Fight on, coach!

A special thanks in the crafting of this article goes to Mal Florence’s “The Trojan Heritage: A Pictorial History of USC Football.” Published in 1980 by JCP Corp. of Virginia.