With kickoff of the 2012 college football season just about 48 hours a way, here’s the third and final reach back into my archives of special columns I wrote for the now defunct PigskinPost.com website during the early part of the last decade. (PigskinPost was swallowed up into the larger — and still existent — CollegeFootballNews.com after the 2003 season).

As a bookend to the story I posted last week about one legendary USC head coach — John McKay — here’s a piece I wrote on another legendary USC headman, Howard Jones. This column was also a part of PigskinPost’s countdown of the Top 50 college head coaches of all time, with Jones ranking No. 23. Here’s to a great 2012 campaign!

(Originally published March 2002 on PigskinPost.com)

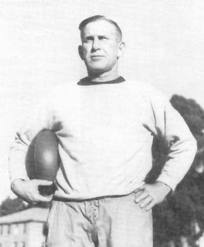

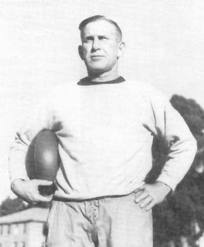

Howard Jones: The Headman Who Created the ‘Thundering Herd’ and Wrote the Opening Chapter of USC’s National Football Tradition

Howard Harding Jones, a.k.a. “The Headman,” arrived on the University of Southern California campus before the 1925 season. But, many believe he was the second choice … to someone whose name a few of you may know.

According to long-time Los Angeles Times’ writer Mal Florence’s book, “The Trojan Heritage,” when USC began looking for someone to replace Elmer C. “Gloomy Gus” Henderson, whose record of 45-7 produced the school’s best winning percentage for any coach in its history, the Trojans’ search started with a certain coach for a certain private Catholic university in Indiana — a guy by the name of Knute Rockne.

1920s-era USC graduate manager Gwynn Wilson (whose name graces the school’s student union to this day), remembers in Florence’s tome, “Rockne came to USC for a football seminar, and we saw a lot of him. We didn’t have a coach, and we talked to Rock about the job. He agreed to come, subject to getting a release from Notre Dame. Mrs. Rockne had fallen in love with Southern California. We had hopes but (Notre Dame) talked him into staying. Maybe it was better that the Rock stayed there, and we got Jones.”

Perhaps Wilson was right. Although USC had come to some regional prominence under Henderson, Jones’ arrival in Los Angeles signaled the beginnings of the famed Trojan character and winning tradition.

Al Wesson, USC sports publicist from 1928-42, told Florence in “The Trojan Heritage,” “Jones was really a character-builder. He did what he thought was right, but he didn’t preach to anyone. The players respected him, but he had very little contact with them except on the field.”

Howard Jones won the first four of USC’s 11 national championships.

Showing his hard nature, and to get the players’ attention, Jones was known to take an offensive line stance in practice to demonstrate his blocking scheme — and then literally pancake the unsuspecting defensive lineman expecting him to walk through the play. But, at the same time, Jones would not swear — on the field, in the locker room, anywhere — and never touched a drop of liquor.

Nick Pappas, who played quarterback for Jones in the 1930s before becoming a USC alumni support fixture, told Florence, “He could stand on the sideline, and he knew what everybody did — or should have done — on every play. When he walked on to the practice field, the atmosphere changed immediately. You might be horsing around but, when he arrived, everybody went right to work without a word being said.”

Before Jones, USC football had won zero national titles and featured no All-Americans. In 16 seasons, Jones coached 19 All-Americans (including African-American lineman Brice Taylor, USC’s first AA), won eight Pacific Coast Conference (PCC) crowns, went 5-0 in the Rose Bowl, had three undefeated teams (1928, 1932, 1939) and won four national titles (1928, 1931, 1932, 1939). He notched an overall record of 121-36-13 at Troy.

Under the Headman, USC played power football out of the classic single-wing formation. Jones’ Trojans became known as the Thundering Herd for their powerful running attack. In this system, Jones developed the prototype for the modern tailback. But in his system, the position was called quarterback. The QB carried the ball 80-90 percent of the time, and also passed, punted and played safety on defense. Among the names that went down in USC lore at the position during the Jones era include: Morton Kaer, Morley Drury, Russ Saunders, Gus Shaver, Orv Mohler, Cotton Warburton and Ambrose Schindler.

While power running was the Trojans’ calling card, Jones did add some spice to the offense at just the right times, like the wingback reverse and a surprise passing attack the Trojans played to perfection in a 47-14 trouncing of Pittsburgh in the 1930 Rose Bowl. Amazingly, with the famed power rushing attack, Jones’ only 1,000-yard rusher was Drury, who gained 1,163 yards in 1927. But all of Jones’ star backs averaged about five yards per carry with many fewer attempts than modern running backs.

Jones came to ’SC after a 4-5 season at Duke, some say on the recommendation of Rockne. But Jones had a stellar resume of his own when he arrived at University Park. Jones was an All-American player at Yale, who then led Syracuse, at age 23, to a 6-3-1 record in 1908 — his first season as a head coach. Jones then split time coaching at Yale and Ohio State, leading an undefeated Yale squad in 1909, until taking the head job at Iowa from 1916-23. He notched two undefeated seasons at Iowa (1921, 1922). And his 42-17 overall record there included an historic 10-7 win against Rockne’s Irish in 1921, ending a 21-game Notre Dame unbeaten streak. But that was just the first of his successful encounters with the Irish.

According to “The Trojan Heritage,” one of the reasons Henderson reportedly had been fired by USC was an inability to beat California. Henderson lost his last four straight to the Golden Bears, while Cal and Stanford administrators questioned Troy’s academic and athletic requirements, due mainly to the Trojans’ rapid ascent after the school joined the PCC in 1922.

Jones didn’t have similar problems against Cal, ripping the Bears 27-0 in his second season and losing only once to Cal in the next seven seasons. The Trojans’ 74-0 victory at the Coliseum in 1930 (a game to which I proudly own a ticket stub) caused Cal to charge USC with “professionalism,” because they claimed the Trojans paid their athletes. The charges were never substantiated beyond mere sour-grape accusations.

Stanford, with Coach Glenn “Pop” Warner, was a tougher assignment for Jones. Jones lost twice and tied once against the Indians before finally prevailing in the Trojans’ 1928 national championship season, 10-0, against a Stanford team that outweighed Troy by 10 pounds per man.

Jones, upon the advice of assistant Cliff Herd (who scouted the Indians all season), created a defense called the “quick mix,” which attacked Stanford’s linemen at the line of scrimmage. This allowed hard-hitting secondary tacklers to get a clear shot at the ball carriers in the Indians’ vaunted reverse attack — a revolutionary scheme in a time where most teams waited for the ball carrier to come to their defensive players at the line of scrimmage. The crashing style of defense forced five Stanford fumbles, of which the Trojans recovered three. Warner never beat Jones again before he left Stanford after the 1932 season.

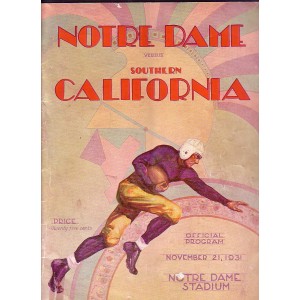

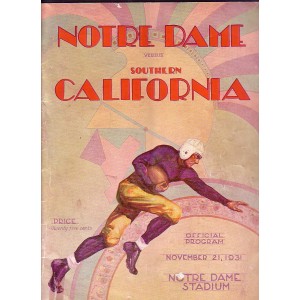

Also during Jones reign, the USC-Notre Dame rivalry began in 1926. 1928 marked USC’s first win against the Irish, a 27-14 thrashing after Rockne’s Irish teams had beaten Jones’ Trojans by one point in each of the prior two meetings. Rockne beat Jones twice more before he perished in a March 1931 plane crash. But what began with Rockne and Jones has lived on as college football’s most tradition-filled rivalry, even in the dark times of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The 1927 USC-Notre Dame game at Soldier Field in Chicago drew 120,000 fans, still the largest crowd ever to watch a college football game. Two years later, nearly 113,000 filled Soldier Field again.

USC’s come-from-behind win at Notre Dame Stadium in 1931 was one of the greatest moments in L.A. sports history.

USC upset Notre Dame in 1931, 16-14, at South Bend, the first of three straight Trojan wins over the Irish — and, many say, USC’s most important victory in its long football history. After the Trojans’ fourth quarter rally from a 14-0 deficit, USC’s train returned to Union Station in Los Angeles, where the Trojan team was celebrated by more than 300,000 Angelenos in a downtown tickertape parade.

USC had a 27-game unbeaten streak from 1931-33. The 1932 Trojans, among the greatest college football teams of all time, were 10-0 and allowed just 13 points to their opponents. Proving that disgruntled alumni are not a modern phenomenon, Jones had those who wanted him cut loose during a four-year downturn from 1934-37 (a combined record of 17-19-6).

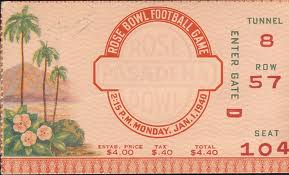

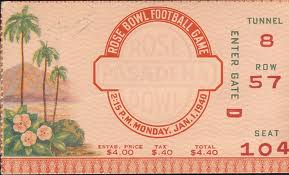

But Jones’ 1938 squad bounced back to 9-2, defeating previously undefeated, untied and unscored-upon Duke, 7-3, in the 1939 Rose Bowl on a fourth-quarter TD pass from fourth-string QB Doyle Nave to end “Antelope” Al Krueger. Then, in 1939, Jones’ Trojans went 8-0-2, capping the season with a 14-0 win over another previously unscored-upon opponent, Tennessee, in the 1940 Rose Bowl.

Jones was also a true believer in sportsmanship. One of the most famous Jones stories related in “The Trojan Heritage” surrounds the 1930 USC-Stanford game. Indians’ star halfback Phil Moffat was considered the key to a Stanford win, but when he went out with a twisted knee on the first play of the game, Jones rushed to the Stanford locker room. There, he asked Moffat if he knew which Trojan had hit him. Moffat, surprised by Jones’ appearance, said yes. Jones then asked him if he’d been hit fairly. After a stunned Moffat didn’t answer, Jones asked him again if he’d been hit fairly, then told the Indian halfback that if his leg was deliberately hit and twisted by the player, that the tackler would never again play for USC. “Moffat said that he had been tackled fairly. Jones said, ‘We don’t want to win any other way on that field.’”

The Trojans’ final national title of the Jones Era was earned in the 1940 Rose Bowl against Tennessee.

Jones died of a heart attack in July 1941 at age 55. USC wouldn’t win another national title for 21 years.

A fitting close to Florence’s chapter on Jones came from the man responsible for hiring the Headman at USC. Many years after Jones’ death, former USC athletic director Willis O. Hunter said, “I’d have to say that all of us hitched our wagon to a star, and Howard Jones was that star. He made all of USC’s later success possible.”

A special thanks in the crafting of this article goes to Mal Florence’s “The Trojan Heritage: A Pictorial History of USC Football.” Published in 1980 by JCP Corp. of Virginia.